Understanding Urbanization: How Urban Growth Affects Ecosystems and Forests

Get news, updates, & event Info delivered right to your inbox:

As human populations continue to grow, so too does our expansion into and fragmentation of ecosystems. Urbanization happens when large numbers of people move into one area; usually from rural to urban areas. And with 68% of the global population projected to live in urban areas by 2050, urban expansion and development isn’t going away.

Over 13 million hectares of forest land are converted to agriculture, urban land use, and industrial forestry (large‐scale, commercial tree planting to produce timber and other wood products) every year. When forested land is developed, it can trigger a chain of ecological effects that echo far beyond the degraded or deforested area. And as ground is broken, pavement is poured and buildings are constructed, important ecosystem services can be significantly diminished — or lost altogether.

Six Impacts of Urbanization

1. Habitat loss

When forests are cleared and land is developed, wildlife habitat is profoundly altered — or lost altogether. This can result in local extinctions of species that rely on specific conditions to survive, shifting population dynamics, increased competition from invasive species, higher stress and mortality rates, and more. Species that live in altered environments are also more vulnerable to fire, pests, and disease.

2. Hydrological changes

Urbanization creates a condition called urban stream syndrome. Increasing storm water runoff, which is caused by the flow of stormwater over impervious surfaces (such as pavement), can alter natural stream flows, change water temperatures, alter the morphology of water features in the landscape, change the quality and quantity of water resources, and more.

3. Reduced water quality

Overburdened urban infrastructure, such as sewer lines, septic systems, and wastewater treatment overflows (or lack of), can add nutrients and organic contaminants (such as pharmaceutical drugs, caffeine, detergents, etc.) to water features. These contaminants can have a profound effect on aquatic ecosystems — and the flora and fauna that rely on them.

4. Climate change

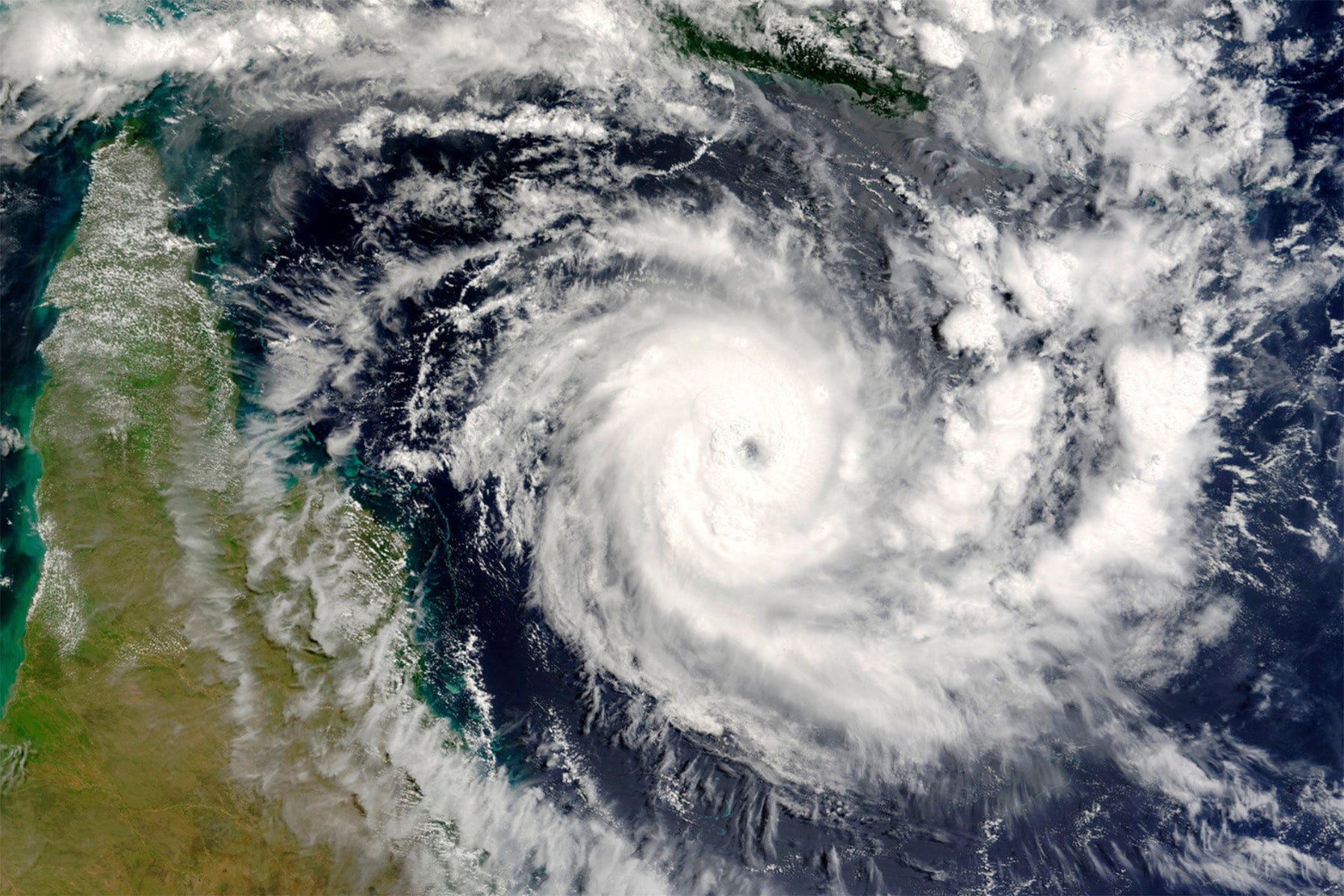

According to the IPCC, in 2020, the world’s urban areas contributed about ¾ of all carbon dioxide equivalent emissions that year. At the same time, urban dwellers are increasingly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, increased precipitation, flooding, intensifying cyclones and storms, and periods of extreme temperatures.

5. Resource demand

As of 2020, there were 31 megacities (cities with populations exceeding 10 million people) and 987 smaller cities (populations between 500,000 and five million people). By 2030, there will be over 41 megacities and 1,290 smaller cities. Building new cities requires massive amounts of raw materials like sand, metals, and wood.

6. Urban heat

Urban heat islands are areas within urban and suburban environments that experience elevated temperatures — especially when compared to rural areas. When homes, businesses and industrial buildings are built close together, they generate, trap and store heat, which significantly increases surrounding air temperatures. In addition to stressing the health of city dwellers (people, wildlife, and plant life), the urban heat island effect can alter precipitation patterns, increase ozone production, and modify biogeochemical processes.

If we continue to build cities the way we historically have (low density, energy and material intensive), at current rates of urbanization and population growth, it will require more raw materials than the planet can sustainably provide. As climate change intensifies and more and more people migrate into concentrated areas, the need for sustainable and integrated urban planning is clear.

Many of the negative impacts of expansion and urbanization can be reduced with careful planning and design. Sustainable and integrated urban design is a holistic approach that combines several aspects of city design and management, including place-making, transportation, housing, health and biodiversity. It means planning with nature, rather than cementing over it — recognizing that our survival depends on coexisting with the biodiversity we share the planet with.

Existing cities can also be improved to make them more livable for people and biodiversity alike. One important strategy? Planting trees. Urban trees are the trees we live with - from individual street trees and urban greenspaces, to shady school groves and downtown orchards. The establishment of thriving urban forests makes our cities healthier places to live, work, and play. And with climate change impacts like intensifying storms and rising temperatures, we need urban trees now more than ever. A few benefits of urban forestry are:

- Improved community health and wellness

- Urban heat mitigation

- Increased climate change resilience

- Protection of water resources

- Youth engagement and education

- Biodiversity and habitat restoration

- Air pollution reduction

- Increased access to recreational opportunities

- Environmental justice and tree equity

Urbanization is a complex issue, and its connection to climate change often gets overlooked. Fortunately, there are strategies that can reduce the impact that growing cities have on the environment — and improve the ones that already exist. Urban forestry is one powerful strategy to improve the “green infrastructure” of cities, and the lives of their inhabitants.

Get news, updates, & event Info delivered right to your inbox:

Related Posts

Sustainable Diet Tips: How to Eat Healthy While Protecting the Planet

13/01/2026 by Meaghan Weeden

Agroforestry Explained: Principles, Benefits, and Case Studies

08/01/2026 by Meaghan Weeden

Plant Your Resolution: Making a Global Impact With The Grove

01/01/2026 by One Tree Planted

Popular On One Tree Planted

How to Reduce Waste: 21 Practical Zero Waste Tips for Everyday Living

23/12/2025 by Meaghan Weeden

Inspirational Quotes About Trees

16/12/2025 by Meaghan Weeden

The 9 Oldest, Tallest, and Biggest Trees in the World

11/12/2025 by One Tree Planted

Fundraising Disclosures

Be Part of the Restoration Movement

The Grove is more than just a monthly giving program: it's a vibrant community of individuals who are dedicated to reforestation and environmental restoration on a global scale.